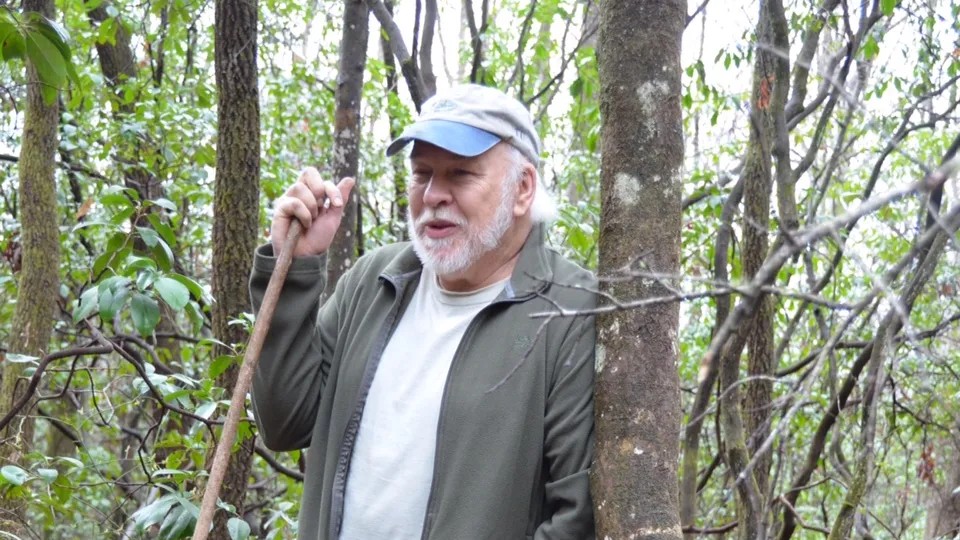

At the 12th Annual BellFest, held on March 22, 2025, at Devils Fork State Park on Lake Jocassee, SCNPS President Dan Whitten delivered a captivating presentation titled “The History and Mystery of Shortia.” In his talk, Dan explored the unique discovery, rich history, and ecological significance of the Oconee Bell (Shortia galacifolia), a rare and treasured native plant of the Southern Appalachians.

BellFest, hosted by Friends of Jocassee, celebrates the blooming of the Oconee Bell and features live music, guided hikes, local vendors, and educational presentations. Dan’s talk was a highlight of the event, offering attendees deep insights into the botanical intrigue surrounding this elusive species.

We are pleased to share the full text of Dan’s presentation below for those who could not attend or who would like to revisit his prepared remarks.

The History and Mystery of Shortia

Presented by Dan Whitten, March 22, 2025

“The fairest bloom the mountains know, is not an iris or a wild rose, but the little flower of which I’ll tell, known as the brave Acony Bell.”

—Gillian Welch, “Acony Bell”

This is a story of the history and mystery of the Oconee Bell, Shortia galacifolia. Shortia is a low-growing evergreen plant that grows near water and on shaded slopes in Oconee and Pickens counties in SC, Jackson and Transylvania counties of NC, and Rabun County, GA. Other populations exist but are thought to be from cultivation. Although it transplants easily, it is very difficult to propagate from seed (see Joe Townsend poster).

It grows from about 700 to 2,100 feet in elevation and blooms as early as late February until mid-April, depending upon location.

There are seven species of Shortia around the world. Three species grow in Japan (one of which is also in Taiwan), a fourth in southern China, and a fifth in Vietnam. But there are two species native to the Carolinas. Its status is imperiled globally but rated S3 in SC. I like to say it is rare but locally abundant.

There are several mysteries involving Shortia. One is solving the collection date and location, and another relates to the fact that, “It was discovered by a man who did not name it (Michaux), named by a man who could not find it (Gray), and named after a man who never saw it (Short).” Following the history of this plant will explain its mysteries.

The Cherokee—now the largest tribe in the U.S.—were well established by the 1720s as the Lower Town in NW SC. They knew Shortia as “Au-quo-nee” or Acony, which is how the English spelling of the Cherokee word goes. It means “beside the waters,” which is where it is found.

William Bartram traveled throughout the Southeast for four years from 1773–1776 and came through Oconee County in 1775. He used the fur trader path connecting the Chattooga River and the Keowee River at Essenca (Clemson, SC). His Travels were published in 1791.

André Michaux, trained in botany by de Jussieu, was sent by the King of France to America to send back trees, shrubs, and plants for the gardens of Europe. He stayed in America from 1785 to 1796. He visited with Bartram in Philadelphia to get a lay of the land and established a garden in NJ and later another in North Charleston, where he based most of his explorations. Michaux traveled widely in those 11 years in America, but I will focus on his travels through Oconee County, which occurred in June 1787 and again in December 1788. He collected many plants and sent some to his gardens and some back to France.

Asa Gray, who we consider the father of American botany, lived from 1810 to 1888. As a teenager, he sent collected and pressed specimens of plants to Dr. John Torrey, who was impressed with Gray’s abilities. They began corresponding and later collaborating on naming new species and writing a flora. Although Gray started out in the medical profession, his interest and lifetime pursuit was botany. He was hired to teach botany at the new University of Michigan in 1838 and was sent on an 11-month journey to Europe to gather books for the new library and teaching materials. He also took advantage of this opportunity by searching out herbaria to work on a book with John Torrey called A Flora of North America. A focus of his was the Michaux collection, since Michaux had botanized from Quebec to the Bahamas in America and had himself written Flora Boreali-Americana, or The Flora of North America.

In 1839, Gray found a cabinet in Michaux’s collection that was called Plantae Incognitae. There he found the unnamed plant that the label said, “Hautes montagnes de Carolinie.” It contained a full plant with a root, leaves, two seed stalks, a stolon, and another rosette of leaves. Also noted on the specimen: “Pyrola?, au genus novum?”—translated: maybe a Pyrola, a new genus? Seeing that it was unnamed, Gray wrote the description and named this plant after his Kentucky friend Charles Short. Since the leaves resembled Galax, the plant was named Shortia galacifolia, Torr. and A. Gray. At age 29, Gray had boldly created a new genus. This became the type specimen for the new species. Gray collected from the herbarium sheet a leaf, a seed capsule, and their stems, along with a sketch that a French associate drew of the plant. This was brought home by Gray and is now in the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University. The only clue to its type location (where collected) was the label on the specimen that stated, “In the high mountains of Carolinas.”

Gray was anxious to substantiate his discovery of a new species and made the first of three trips to search the high mountains of the Carolinas in 1841, after resigning from the University of Michigan due to financial issues. He was hired in 1842 at Harvard. Again in 1843, Gray made another trip to the high mountains of Carolina, and again in 1876. In all of these trips he did not find Shortia. But I would say these trips did not come up empty. Gray discovered and named many new species. He is credited with naming approximately 1,000 species in his lifetime.

Charles Sargent graduated from Harvard in 1862 (age 21) and in 1872 became the first curator of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum in Boston, Mass. He held this position until his death in 1927 (age 85).

On April 1, 1877, 90 years after Michaux’s find, 17-year-old George Hyams was on a field trip with his father Mordicai Hyams (an amateur botanist). They were collecting pharmaceutical herbs for Wallace Brothers, a Statesville, NC company. George found the flowering plant—which had been the “Holy Grail” of many botanists for 38 years—along a tributary of the Catawba River in McDowell County, NC. Mr. Hyams, not knowing the plant, collected and pressed the specimen and sent it to Joseph Condon in RI, who suspected that it might be Shortia. The specimen was then sent to Asa Gray in 1878, who was ecstatic to once again see the plant that he feared may have become extinct. He hollered, “Eureka! Eureka!”

The next year in 1879, a fourth expedition was formed with Asa Gray, Charles Sargent, William Canby, John Redfield, and others (Mrs. Gray, her brother, and two daughters) to visit the Hyams and see the Shortia. When they made the final part of the journey from Marion, Mordicai stayed in town with the colic and sent his son George to show the party the Shortia location. John Redfield wrote in his book In Search of Shortia: “We carefully abstained from doing anything that might lessen future supply, but we four did lie there for a while in the cooling shade enjoying the sight and the rest; ‘gloating,’ in fact, over this little patch not over 20 feet in extent which contains (so far as we yet know) all of this plant which the world furnishes.” (June 9, 1879)

In 1886, seven years later, Charles Sargent had Michaux’s journal transcribed and was searching for what Michaux had called Magnolia montana and Bartram called M. cordata or M. auriculata. We now call this Magnolia fraseri, or Mountain Magnolia. Sargent was the curator of an arboretum and a tree lover like me. This journey took him to the confluence of the Horsepasture and Toxaway. There he found Mountain Magnolia and rediscovered the Shortia growing there. He was convinced that this was what Michaux called “the head of the Kiwi—the junction of two torrents of considerable size which flow by cascades from the high mountains.” Sargent thought that Michaux’s collection of “un novel arbuste” or a new shrub collected twice in Dec. 1788 (the 8th and the 11th) was the same Shortia named by Torrey and Gray. Michaux describes the shrub on the 8th as having “denticulated leaves, climbing on the mountain a short distance from the river.” And then on the 11th: “I collected a large quantity of the shrub with notched leaves that I found the day I arrived. I did not meet it on any of the other mountains.”

In 1947, A.E. Prince noted that Sargent did not explore the Whitewater and Toxaway confluence, or he might have thought this was the “head of the Kiwi.” Prince made three trips to the Keowee River and expressed his opinion that Michaux’s “head of the Kiwi” was near the junction of the Whitewater and Toxaway Rivers.

In 1952, P.A. Davies described and named two different varieties of Shortia galacifolia. He called the McDowell County population Shortia galacifolia var. brevistyla and the Jocassee population Shortia galacifolia var. galacifolia.

Then in 1956, Davies published the Type Location of Shortia Galacifolia in Castanea. Based on a drawing of the type specimen and the material that Gray brought back with him, and using his previous study of the style variations, he concluded that the type specimen had to come from the Keowee population and not the Catawba population. This meant it had to be either the 1787 or 1788 journey of Michaux when it was collected. Davies looked closely at both Sargent’s and Prince’s arguments and concluded that the type specimen was collected on June 14, 1787, at the Horsepasture and Toxaway confluence—Michaux’s first trip to the sources of the Keowee.

In 1970, Lake Jocassee began to fill, and the first generation of power began in 1973 by Duke Power (now Duke Energy) when the lake was full. An estimated 60–80% of the Oconee Bells were lost.

In 1976, Margaret Mills Seaborn of Walhalla published Journeys of Andre Michaux in Oconee County, 1787 & 1788. She had translated Michaux’s journals and worked out the dates and places and made a map of both journeys. She also concluded that the type specimen of Michaux was collected on Dec. 8, 1788, from his journal entry that day: “approaching the source of the Kiwi…we stopped there to camp and I rushed to do some exploring. I gathered a new low plant with saw-toothed leaves spreading over a hill a short distance from the river.” Also in his journal was an entry describing the taste and smell of the leaves: “The Indians of the place told me that the leaves had a good taste when chewed and the odor was agreeable when they were crushed, which I found to be the case.” Asa Gray also added a note to his copy of the Sargent 1886 publication, commenting on the taste and smell: “Michaux must have had reference to Gaultheria procumbens (Wintergreen or Teaberry) and not Shortia, for the foliage is slightly mucilaginous and odorless.”

In 1983, Robert Zahner and Steven Jones published a report in Castanea that resolved the location and date of the type specimen collected by Michaux and named by Torrey and Gray. Jones did a phenology study of Shortia populations in the Jocassee Gorges. He observed the plant throughout the growing season for several years and found that the seed capsules are gone by the end of June. Jones concluded that the Michaux type specimen could not have been collected on Michaux’s second trip to Oconee County in Dec. 1788. That trip was for “tubbing” or potting of trees and shrubs in the dormant season for shipping to Charleston and to Europe. Zahner looked closely into verifying, on the ground, the Seaborn maps and translated journal entries and dates. He also verified the distances recorded in the journal and place descriptions. He looked closely at a week’s travel that began and ended at Seneca (Clemson), starting on June 11, 1787. The journal entry on the 12th has Michaux complaining of not finding any new species since May 8 on his way up the Savannah. He was camped just south of the Shortia habitat on the west bank of the Kiwi (Keowee) River. The next day was 14 miles, and 6 or so miles of it were right through the heart of the Shortia range. But the only journal entry contains his excitement at finding Buffalo Nut and Cucumber Magnolia, which he had not seen before. Zahner believes he had to have collected the single specimen at that time even though there was no entry about this. During the 13th, he crossed the Kiwi (now the Whitewater) River before the confluence with the Toxaway River, which was unnamed on the maps of that time. He proceeded to cross the Tugalo (Chattooga) River and came to the Tenasa (Little Tennessee) River before turning back because of bad weather and returning via the fur traders’ path that Bartram had used 12 years earlier, arriving back in Seneca (Clemson) on June 18. Zahner concludes that Michaux had to collect the type specimen on June 13, 1787, in that 6-mile stretch along what we now call the west bank of the Keowee River and the north bank of the Whitewater River. No population of Shortia exists above the 1,110-foot waterline of present Lake Jocassee along the Whitewater River. Also, this being Michaux’s first trip up the Savannah watershed, from Seneca and above, you can see what he probably considered the high mountains before ever having traveled into them.

In 1990, Devils Fork State Park was established. The Oconee Bell Trail opened in 1991.

In 2004, Charlie Williams of the Michaux Society (and twice a BellFest speaker) and others went to Paris and located a second specimen of Shortia that was in the private collection of de Jussieu. This was the man who trained Michaux in botany, and this previously unknown specimen was gifted to him by Michaux. This collection had been donated in 1857 to the Paris Herbarium but was not with the Michaux collection.

In 2012, Friends of Jocassee obtained their 501(c)(3) status. We have funded the installation and materials for the boardwalk on the Oconee Bell Trail to protect against soil compaction due to walking and lying on the ground to get that cherished photo. Instead, use zoom or macro to get up close. We installed safety grids on the bridges, installed over 60 plant signs with a QR-coded brochure to go along with it. We have funded and cared for the water feature at the park office and placed Shortia there. We have helped fund the purchase of property along Boones Creek to protect a Shortia population from development.

In December 2012, National Geographic special edition came out entitled “50 of the World’s Last Great Places, Destinations of a Lifetime.” Jocassee Gorges was included as one of the features of the temperate zone.

In 2013, the first BellFest was held.

In 2019, Dr. L.L. Gaddy determined, due to geographical, morphological, and molecular differences, that Shortia brevistyla is a distinct species from S. galacifolia. The McDowell County population has a 10 km radius from the type location, and the Jocassee Gorges population has a 15 km radius from its type location in Oconee County just north of the Jocassee Dam. The closest of each population is at least 100 km apart. S. brevistyla has shorter styles and petals, and its leaves and flowers are smaller. The best field character is the shallow, blunt teeth of petals of S. brevistyla compared to the deeply toothed petals of S. galacifolia. Now the common names are Northern Shortia and Southern Shortia, or Oconee Bells. This caused me to change some labels on the trail signs.

In 2025, the 12th annual BellFest event was held (with 2021 being online only). Now it is 238 years since Michaux collected the type specimen of Shortia on June 13, 1787, just upstream from the present Jocassee Dam. Michaux found it but did not name it; Gray named it but could not find it for forty years; and Short never saw it. In fact, all three men never saw it bloom in the wild. I hope you all have plenty of opportunity to do so today at BellFest.

“Well it makes its home mid the rocks and rills

Where the snow lies deep on the windy hills

And it tells the world, ‘Why should I wait?

This ice and snow’s gonna melt away.’

And so I’ll sing that yellow bird’s song

For the troubled times will soon be gone.”

—Gillian Welch, “Acony Bell”

So be sure to see this Au-quo-nee, this Shortia, this Oconee Bell, this “Harbinger of Spring,” in one of the world’s last great places—right here in the Jocassee Gorges, in Devils Fork State Park.

Sources:

-

Flora of the Southeastern United States, Edition April 14, 2023 – Alan Weakley & Southeastern Flora Team

-

Phytologia (June 21, 2019) 101(2) – L.L. Gaddy, T.H. Carter, B. Ely, S. Sakaguchi, A. Matsuo, Y. Suyama

-

Castanea, Vol. 21, No. 3, Sept. 1956 – P.A. Davies, “Type Location of Shortia galacifolia”

-

Rhodora, 54:124, 1952 – P.A. Davies, Shortia galacifolia var. brevistyla

-

Oconee Bells Celebration, March 16–18, 2007 – Clemson University

-

Journeys of Andre Michaux in Oconee County, 1787 & 1788 – Margaret Mills Seaborn

-

Gillian Welch, “Acony Bell” (song)

-

Charles Sprague Sargent, 1886 – Type Location of Shortia galacifolia

-

Castanea, Vol. 48, No. 3, Sept. 1983 – R. Zahner and S. Jones, “Resolving the Type Location of Shortia galacifolia, Torr. & A. Gray”

-

Donald H. Pfister, Harvard University, 2017 – Asa Gray and the Quest for Shortia galacifolia, 4/10/2017

-

Rhodora, 49:159–161, 1947 – A.E. Prince, “Shortia galacifolia in Its Type Range”

-

“Shortia galacifolia, the Most Interesting Plant in America” – Kay Wade PowerPoint, March 2020