by Dr. Jon Storm

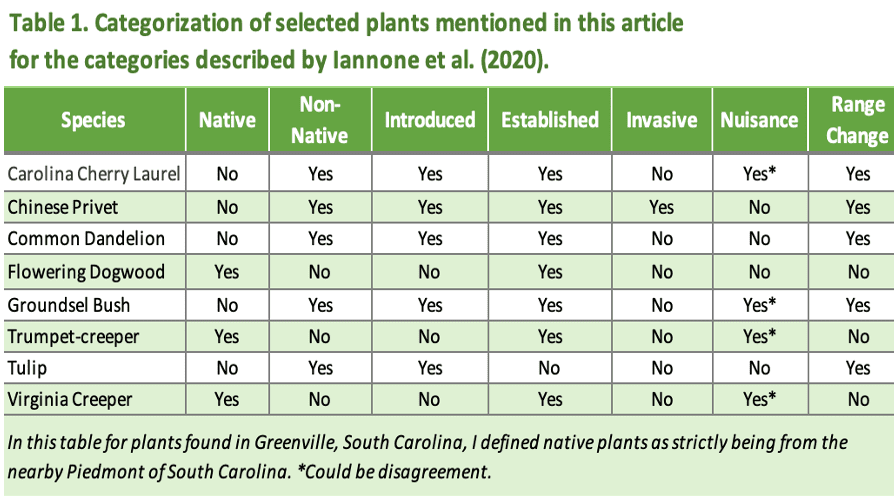

You may have heard people call plants like Trumpet-creeper (Campsis radicans) “invasive,” yet the same term is used for Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense). The use of “invasive” can be confusing as Trumpet-creeper is native to the Upstate of South Carolina, whereas Chinese Privet is from Asia. There’s no need to fret over proper terminology, though. A recent scientific paper by Iannone et al. (2020) in The Journal of Extension sought to establish standard definitions for native and non-native species and their effects on the environment. Their seven recommended terms are: native, non-native, introduced, established, invasive, nuisance, and range change. The use of each is described below, along with a list of representative organisms from the Upstate of South Carolina that are best represented by each term. The paper by Iannone et al. is linked in the References.

What’s a Native Plant?

A Native Plant evolved in the region of interest and was present prior to European settlement.

This term encompasses many of the plants familiar to members of the South Carolina Native Plant Society. These are the ones we seek to grow in our yards to support pollinators and provide food for caterpillars. There can, however, be confusion with the term “native” and the timeline of human influence on the movement of plants. For instance, the Peach tree (Prunus persica) was introduced to the United States by Spanish explorers in the 16th Century and may have been present in the United States before the first European settlement at St. Augustine in 1565. Still, the Peach would not be considered native as it did not evolve in the southeast, it evolved in Asia.

In my opinion, the main area of potential disagreement is how to define the “region of interest” for a native plant. Consider someone living in Greenville, South Carolina. Is a native plant restricted to just those from the Southern Outer Piedmont Ecoregion or the Southeastern Mixed Forest ecoregion? Would native plants include the entire Piedmont of South Carolina or maybe even the entire state? The southeast? All of North America? See where this can become subjective?

What’s a Non-native Plant?

A Non-native Plant did not evolve in the region of interest and was generally introduced after European settlement.

Saying a species is non-native does not imply that it’s invasive, nor does it mean it has become established in the natural environment (i.e., it has naturalized). Many plants used in horticulture are non-native, including Chinese Wisteria (Wisteria sinensis), Common Daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus), Common Lantana (Lantana strigocamara), Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), Leatherleaf Mahonia (Mahonia bealei), Ornamental Cabbage (Brassica oleracea), and Southern Indian Azalea (Rhododendron indicum).

There are more than just non-native plants in the Upstate, such as the Brown Marmorated Stinkbug (Halyomorpha halys) found around gardens, the Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) in rivers, the European House Mouse (Mus musculus) that lives around homes, the Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) living under bridges, and the Chestnut Blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) that led to the demise of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata).

What’s an Introduced Plant?

An Introduced Plant was brought into the area by humans either by intent or by accident.

An introduced plant is non-native; however, this does not mean it’s invasive or established in the natural environment. There are many introduced plants in the Upstate, including Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense), Common Daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus), Crape-myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica), Geranium (Pelargonium x hortorum), Inch Plant (Tradescantia zebrina), or Pansy (Viola x wittrockiana).

There are also many introduced animals in the Upstate, including the American Cockroach or “Palmetto Bug” (Periplaneta americana), Asian Lady Beetle (Harmonia axyridis), Joro Spider (Trichonephila clavata), and Hammerhead Worm (Bipalium kewense) from Asia or the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and Rock Pigeon from Eurasia.

What’s an Established Plant?

An Established Plant has a self-sustaining and reproducing population that can survive in the natural environment without human assistance.

An established plant could be either native or non-native, but it typically refers to non-native species. Being established does not necessarily mean the plant is invasive, it simply means it can survive in the wild on its own. Some folks may use “naturalized” as a synonym for established. Obviously, there are gray areas regarding whether certain species are established, and a plant that’s established in one region might not be established in another.

There are many established plants in the Upstate, including the Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare), Common Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule), and Purple Deadnettle (Lamium purpureum). Each are native to Eurasia but are common today in fields, roadsides, abandoned lots, and other disturbed habitats.

Many introduced (and therefore also non-native) species do not spread beyond where they were planted and would not be considered as established in the natural environment. These species simply persist for a while where they were planted and could indicate an old homestead. Plants listed as “persisting” or “waif” in Weakley’s Flora of the Southeastern United States would fit this description. Tulips (Tulipa spp.) and German Iris (Iris germanica), for instance, would be introduced, but not established, plants.

Established animals in the Upstate would include the Chinese Mantid (Tenodera sinensis), Rock Pigeon, and European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris).

What’s an Invasive Plant?

An Invasive Plant is non-native, introduced, and causes measurable harm to the natural environment, economy, or humans.

These are the non-native plants we spend a lot of time and effort trying to control in the Upstate. Bradford Pear (Pyrus calleryana), Chinese Privet, English Ivy (Hedera helix), Japanese Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), and Thorny Olive (Elaeagnus pungens) all fit this description. The key point is that an invasive plant must also be non-native.

There are several invasive animals in the Upstate as well. For instance, House Sparrows were introduced from Europe and can outcompete native Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis) for tree cavities and nest boxes. This competition for nesting sites was one cause of the rapid decline of Eastern Bluebirds during the mid-20th Century. Emerald Ash Borers (Agrilus planipennis) and the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae) are also invasive species.

What’s a Nuisance Plant?

A Nuisance Plant is native to the area but may be difficult to manage or control in a desired manner.

This term is the native plant counterpart to an invasive species. It’s also the term that needs to be adopted to prevent confusion by the public. There is some gray area here, though. Depending on the management interests of the individual, a plant may be considered a nuisance by one person and not by another. In general, nuisance plants have undesirable traits such as spreading quickly or sending up lots of suckers. These habits can make them a bit of their namesake nuisance for landowners. Some people would consider nuisance plants to include Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), Eastern Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana), Greenbriar (Smilax spp.), Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), Trumpet-creeper, and Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia).

There are several animals that fit the bill as a nuisance, at least in some instances. This includes Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata), Canada Geese (Branta canadensis), and White-tail Deer (Odocoileus virginianus).

What is a Distribution Range Change for a Plant?

A Range Change occurs when a plant (either native or non-native) changes in distribution either naturally or by human influence.

Some native plants are experiencing a natural shift in distribution within the United States due to climate change. Iannone et al. (2020) stated that these should be seen as natural adaptations to an altering climate and that these plants should not be viewed as invasive or non-native within their new range.

A more contentious view may come from species that are experiencing a range shift due to a more direct human influence. For instance, Carolina Cherry Laurel (Prunus caroliniana), Groundsel Bush (Baccharis halimifolia), and Wax Myrtle (Morella cerifera) have all expanded their range into the Piedmont. Horticultural plantings, logging, roadside mowing, and other disturbances play a role in these recent range shifts. Similarly, Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda) has expanded its range inland due to the timber industry. Some historical records suggest Loblolly Pine was originally restricted to scattered bottomland populations with infrequent fires.

Chickasaw Plum (Prunus angustifolia) is another species that may have experienced a range shift. It’s often listed as a native tree of the Piedmont, but the original distribution is unknown. Chickasaw Plum may have been introduced here by Native Americans from states further west. Consider, for instance, the writing of naturalist William Bartram, who explored the southeast from 1773 to 1777. Bartram wrote, “The Chicasaw plumb I think must be excepted, for though certainly a native of America, yet I never saw it wild in the forests, but always in old deserted Indian plantations: I suppose it to have been brought from the S. W. beyond the Missisippi, by the Chicasaws.” In the instance of Chickasaw Plum and some other species, determining how to define them as native or introduced is not always simple.

Many animals have experienced natural range shifts too. In today’s age, it’s hard to completely exclude human effects, but these shifts are often the result of a warming climate or alterations to the landscape. For instance, Coyotes (Canis latrans) and Armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) have spread across the southeast in recent decades and Groundhogs (Marmota monax) have been expanding eastward across the Piedmont. Western Cattle Egrets (Ardea ibis) can be seen during their migration through the Upstate. These egrets are native to Africa, yet somehow reached South America in 1877 and established breeding populations in the United States by the 1950s.

Focusing on the Big Picture

Despite the best efforts of Iannone et al. (2020) to categorize species, there will be some disagreement regarding the use of these terms. It’s always hard to fit the complexity of the natural world into tidy human definitions. Still, I think there is more agreement than disagreement regarding what constitutes a plant being native or invasive. Hopefully the use of consistent terminology will help us communicate with the public about native plants and the wildlife communities they support.

Selected References

Bartram, W. 1791. Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida. November 5, 2024. http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/bartram/bartram.html

Holland-Lulewicz, J., Thompson, V., Thompson, A.R. et al. 2024. The initial spread of peaches across eastern North America was structured by Indigenous communities and ecologies. Nature Communications. 15: 8245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52597-8.

Iannone, B. V., Carnevale, S., Main, M. B., Hill, J. E., McConnell, J. B., Johnson, S. A., Enloe, S. F., Andreu, M., Bell, E. C., Cuda, J. P., & Baker, S. M. 2020. Invasive Species Terminology: Standardizing for Stakeholder Education. The Journal of Extension. 58: Article 27. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol58/iss3/27

Nesom, G.L. 2000. Which Non-native Plants are Included in Floristic Accounts. SIDA, Contributions to Botany. 19: 189-193.

Weakley, A.S., and Southeastern Flora Team. 2024. Flora of the southeastern United States Web App. University of North Carolina Herbarium, North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill, U.S.A. https://fsus.ncbg.unc.edu/ Accessed Nov 5, 2024.